Some folks were just born hot, others were made that way, often with silicone and an airbrush. So what should mortals who don’t score a perfect ten be doing on Valentines Day? Rob Brooks and Alex Jordan derive three big insights from evolutionary biology that suggest that for those of you on the lookout for somebody, things needn’t be as dire as they sometimes look.

As Valentine’s day approaches, expect the usual retreaded media stories about the sex lives of celebutantes, how to look your best, and the science of attractiveness. Online dating sites are also preparing for the biggest day of their year, as folks look for that special someone/friend/friend with benefits. A short visit to a site like hotornot.com can give the impression that each of us fits somewhere on a single attractiveness scale from HOT to NOT. It is an impression moulded by the magazines and movies we devour, where the fatuously fabulous score a 10 and the rest of us make up the numbers.

Evolutionary research can do a similar thing too. I call this the widowbird paradigm. If you’ve ever visited southern Africa in the summer you will have seen at least one male long-tailed widowbird flapping just above the veld, like a swimmer trying butterfly for the first time. The curious birdwatcher cannot help but wonder how such a burdensome tail might have evolved. In one of the coolest and cleverest early studies on mate choice, Malte Andersson enquired whether long tails might confer an advantage by attracting mates. He cut the tails of male widowbirds, then glued the tails back at either their original length, shorter than they originally were, or longer than they originally were. He also kept another group completely intact.

Andersson found that birds with lengthened tails attracted two to four times as many females to mate with them and nest in their territories, compared with control birds and those with shortened tails. In so doing, Andersson provided clear experimental evidence that the most ornate yet apparently useless features, like widowbird tails, can evolve because they confer an irresistable sexiness on the bearer – a form of natural selection that Darwin called sexual selection. Widowbirds and other long-tailed birds spent the last three decades at the top of the sexual selection charts, because their sexy ornaments are simple to work with (just bring superglue and a pair of scissors) and vary in only one major dimension (length).

We have learned much about attraction, mate choice and sexual selection from the elegant simplicity of long-tailed birds, but studies in other animals – especially humans – don’t always embrace the remarkable complexity of attraction. A lot of human mate choice work has focused only on one dimension at a time. Studies of how waist and hip width influence women’s attractiveness provide possibly the most famous example. In 1993 the late Devendra Singh published a paper in which he manipulated line drawings of female figures and showed that figures drawn with a waist that was 70 percent as wide as their hips (a waist-hip ratio, or WHR of 0.7) were more attractive than figures that deviated from these proportions. Singh’s paper has been cited by more than 550 other studies in the last 18 years, many (but by no means all) of which support the idea that a WHR of around 0.7 is optimally attractive. And magazines from Cosmo to O, the Oprah Magazine have consistently churned out stories about this magical proportion.

But what happens to those of us whose waists aren’t optimally narrow, whose chins aren’t perfectly square and who can only rack up a 6, or even a 2 on hotornot.com? As our Valentines day gift to the world, we consider three evolutionary insights that might console those of us who don’t score a perfect “10”. The ones, as Leonard Cohen put it, “like us, who are oppressed by the figures of beauty”[i]. Evolution, it turns out, is about more than winners and losers. Despite what some critics might say, modern evolutionary biology has a sophisticated take on complexity, variation and context. Here are three liberating insights from evolutionary biology:

1. Saved by monogamy

Monogamy isn’t everything that clerics, conservatives and reactionaries often claim it is, but it has its benefits. If it were possible for men and women to mate and pair up with one another, unfettered by conventions and marriage laws, one might expect the most attractive people of one sex to get all the matings. That kind of thing still happens in our short-term relationships, where men like Mick Jagger and Tiger Woods get much more than their fair share. But the fact that we usually pair-up and devote most of our sexual attention to one person at a time gives even the least attractive among us hope.

When Angelina Jolie paired up with Brad Pitt, both unequivocally 10’s on the Hot or Not scale, they shattered the ambitions of men and women everywhere. But as the 10’s find one another and pair up, so the folks who might rate an 8 or 9 become the most desirable available options, and they tend to pair up with other 8’s and 9’s. Because both men and women choose whom to mate with, and because each looks to do the best they can, people very quickly fall into a pattern of assortative mating – where like mates with like. The most attractive folks end up together, people of average attractiveness end up with partners who are similarly average and the folks who are least attractive tend to end up together too. When there are roughly equal numbers of women and men, it turns out that there is somebody for everybody

2. More than one way to be attractive

That might not offer much comfort to those of us who think we might be nearer to 1 than to 10 on the hotness scale. But it’s worth exploring whether attractiveness really is so terribly one-dimensional. There is plenty of evidence that people differ in what they find attractive – perhaps beauty really is in the eye of the beholder.

Or the nose. When Klaus Wedekind and his Swiss collaborators showed that women prefer the smell of genetically dissimilar men, we suddenly had an explanation for why, when you get very very close to some special people, something alchemic seems to happen in your tummy. Other folks, however, don’t have that same effect. A preference for dissimilarity means that there is no single most attractive-smelling person (except, a friend of mine conjectured, the Old Spice guy).

Likewise, our own research on the evolution of human body shape (visit www.bodylab.biz) is showing that there is more than one way to make an attractive body. Attractive bodies can be small, slender, lanky, curvaceous or any one of a great many combinations. Our recent paper, titled Much More than a Ratio shows that leg and arm length and width, bust size, waist and hip size and overall height all interact with one another to influence a woman’s attractiveness. For example, a big bust only enhances a woman’s attractiveness if she also has a slender waist, and slender arms.

3. The importance of a Beautiful Mind

Of course, the most important sex organ in humans is the brain, and Geoffrey Miller’s exceptional and entertaining book The Mating Mind made the case that human intelligence is, in large part a by-product of sexual selection favouring those of our ancestors who were smart enough to impress, woo and seduce the best mates. A beautiful mind is undoubtedly the most attractive feature any of us can offer, irrespective of how we look, sound or smell. But here we are being a little bit more literal – we mean the movie A Beautiful Mind – in which Russell Crowe plays Nobel-winning economist John Nash. In particular, we mean the barroom scene where Nash apparently has his epiphany about game theory – that each man should adjust his courtship strategy in relation to what which women each of his competitors decides to court.

Some wonderful recent analysis by the people behind the dating site OkCupid.com illustrates just how powerfully game theory changes the way we should look at attraction. They have very kindly permitted us to use the images from their blog post here.

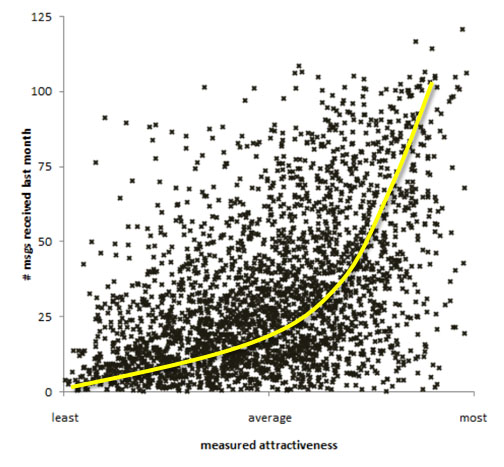

OkCupid visitors are asked to rate photographs of other users using a five star system. If one user wants to make contact with another, they send them a message within the website. Women who tend to get the highest ratings also get the most messages – usually four times as many as women of average attractiveness and 25 times as many as the least attractive users. The graph below shows this relationship for 5000 women on their site.

I added the yellow line to describe the kind of relationship that typifies the widowbird paradigm – the amount of interest a woman gets rises steadily with her attractiveness on the 5-star scale. But it is immediately obvious that there are very hot women getting very few messages, and below-average looking women getting more than 100 messages a month.

Christian Rudder and his colleagues at OkCupid wanted to get a better handle on this mysterious variation, and the first place they looked was at how each woman arrived at her average attractiveness score. One woman, let’s call her “Jemima” could be rated a “4” on average if everybody thinks she’s cute and gives her 4 stars. Another woman (“Dorothy”) might get 5 stars from each of eight men, but only 1 star from the other two men. Some women do tend to get the vague Jemima-like tick of approval, whereas others (like Dorothy) really divide opinion (Look at the OkTrends post to compare pictures of real women who had similar average ratings but vastly different numbers of messages). The big news is that Dorothy and other women who divided opinion tended to get far more messages than Jemima and others who men tended to rate similarly. In fact, as Rudder puts it “the more men as a group disagree about a woman’s looks, the more they end up liking her”.

It’s one of those insights that is so important that it seems obvious, once you’ve seen it. Dorthy, who rates an average of 4 stars despite being ranked only 1-star by a fifth of men, must have some pretty strong admirers. These men are motivated to send her messages, but the men who all rate Jemima a “4” are less motivated to message her. After all, we don’t have to be attractive to everybody – just one person.

Rudder reckons that a game theory explanation, like Nash/Crowe’s epiphany in the pub might be the key to explaining this.

“Suppose you’re a man who’s really into someone. If you suspect other men are uninterested, it means less competition. You therefore have an added incentive to send a message. You might start thinking: maybe she’s lonely. . . maybe she’s just waiting to find a guy who appreciates her. . . at least I won’t get lost in the crowd. . . maybe these small thoughts, plus the fact that you really think she’s hot, prod you to action. You send her the perfectly crafted opening message.”

He turns this insight into some pretty useful and potentially liberating advice: “take whatever you think some guys don’t like – and play it up”. As writers of romantic comedies know, often our quirks and the features we tend to hide become our most enduring assets. A chubbiness, a knobbly chin, sticky-outy ears or a nose that’s so asymmetric you’re often mistaken for a Modigliani model. Your quirky sense of humour (but don’t push it), raw-food veganism or esoteric politics might just find a suitable match better than being a gray nobody. And you can play those quirks up by making sure your tattoos, piercings and odd fashion sense find their way onto your profile pic.

Postscript: The OkCupid analysis is not part of a controlled experimental study and it hasn’t been peer-reviewed, so treat it with more than the usual degree of caution. But new studies and theoretic models, some from Alex Jordan’s recently submitted PhD thesis are finding that exactly this kind of thing happened in the animal world, and presumably also in humans.

[i] From Chelsea Hotel No 2.